Interruption Testing

Published: 2022-02-20

This post is an attempt to capture a general description of a simple testing technique I have encountered in a few guises — and “Interruption testing” is my attempt to give it a name.

Interruption testing is useful when:

- You have a (deterministic) procedure that is comprised of a series of steps. (A prerequsite is that you have a way to inject code to interrupt the procedure at any point, and a way to isolate the component being tested so that you can run it repeatedly.)

- You want to ensure that, no matter where in the sequence of steps that the procedure is interrupted, you can successfully “recover” (with exact meaning dependent on the scenario) from the interruption.

The TL;DR general testing procedure is:

- To create some kind of counter that records the number of “steps” taken.

- To run through the entire operation and see how many steps it takes to successfully complete, call this

N. - Then to exhaustively run through all

Mfrom1..N, running the process from start to finish but interrupting the process at stepM, and ensuring that the process can then recover and complete successfully.

(Alternately, you can do without the initial run and interrupt at 1, 2, … until it succeeds.)

This is a simple technique but I haven’t seen it discussed much anywhere. The first place that I encountered it (I believe) was in Dave Abraham’s article about exception safety in C++, “Lessons Learned from Specifying Exception-Safety for the C++ Standard Library”, where he attributes the technique to Matthew Arnold.

Later update: Graham Christensen reminded me that this technique is used by SQLite, who categorize it as “anomaly testing” on their testing page. They have good descriptions of how it is used to make code robust against OOM conditions and I/O errors, and to ensure recoverability after crashes.

Example 1: Testing for exception-safety in containers

For context, and those who are not C++ programmers, C++ has a concept named “exception safety” that is used to describe the behaviour of a component (class, method, function) when an exception is thrown during processing.

The guarantee comes in several variants:

- the basic guarantee is that all invariants of the component are maintained (and memory is not corrupted, etc),

- the strong guarantee is that either the operation completes fully or (if an exception is thrown) it does not complete at all, and the state of the component is exactly the same as it was before the operation began — i.e. that the operation is atomic.

Most C++ containers in the standard library provide the strong exception guarantee. But how do we test this?

One method is as follows:

Firstly, we create a type that we can use to track the number of “steps” performed. In the case of C++ containers, each step is going to be an invocation of the type’s copy constructor or copy assignment operator.

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

// a well-known error type to throw

class explode: public std::runtime_error {

public:

explode(): std::runtime_error("exploded") {}

};

// interruptor explodes after being copied explode_at times

// (or doesn’t, if explode_at is 0)

class interruptor {

std::shared_ptr<int> counter_;

int explode_at_;

void copied() {

if (++*counter_ == explode_at_) {

throw explode();

}

}

public:

interruptor(std::shared_ptr<int> x, int explode_at=0)

: counter_{std::move(x)}

, explode_at_{explode_at} {}

interruptor(const interruptor& other)

: counter_{other.counter_}

, explode_at_{other.explode_at_}

{ copied(); }

interruptor& operator=(const interruptor& other) {

counter_ = other.counter_;

explode_at_ = other.explode_at_;

copied();

return *this;

}

};

Next we write our test operation. In this case, let’s assume we want to ensure that the std::vector function insert(position, value, number) either inserts number copies of value, or doesn’t insert anything at all (the strong exception guarantee).

We can configure our test function to interrupt after any number of steps via the explode_at parameter:

int insert_is_atomic(int explode_at=0) {

const auto copies = 100;

auto exploded = false;

const auto counter = std::make_shared<int>(0);

interruptor value{counter, explode_at};

std::vector<interruptor> vector;

try {

vector.insert(vector.end(), copies, value);

} catch (explode&) {

exploded = true;

}

// assert atomic condition - either all were inserted or none

if (exploded) {

if (vector.size() != 0) {

throw std::runtime_error("insert was not atomic");

}

} else {

if (vector.size() != copies) {

throw std::runtime_error("insert did not insert all copies");

}

}

// safety check to ensure that everything worked properly

if (explode_at != 0 && !exploded) {

throw std::runtime_error("explode was not triggered");

}

return *counter;

}

Finally, we can execute our test exhaustively as follows:

int main() {

const auto steps_count = insert_is_atomic();

std::cout << "Total steps needed: " << steps_count << std::endl;

for (auto i = 1; i <= steps_count; ++i) {

std::cout << "Interrupting after: " << i << std::endl;

insert_is_atomic(i);

}

std::cout << "Test was successful" << std::endl;

}

First we run through and record how many steps (steps_count) it requires to fully complete succesfully, then we run the operation again once for each step count from 1 through to steps_count, and ensure that the condition we are testing (that insert is atomic) holds each time.

We can also use this to check weaker forms of exception-safety, but often we would need access to the internals of the classes in question to assert basic features such as “all invariants hold”.

The same technique could be used in (for example) Rust, to ensure that containers are “panic-safe” when a type is cloned a certain number of times.

Example 2: Testing for recoverability of message processing services

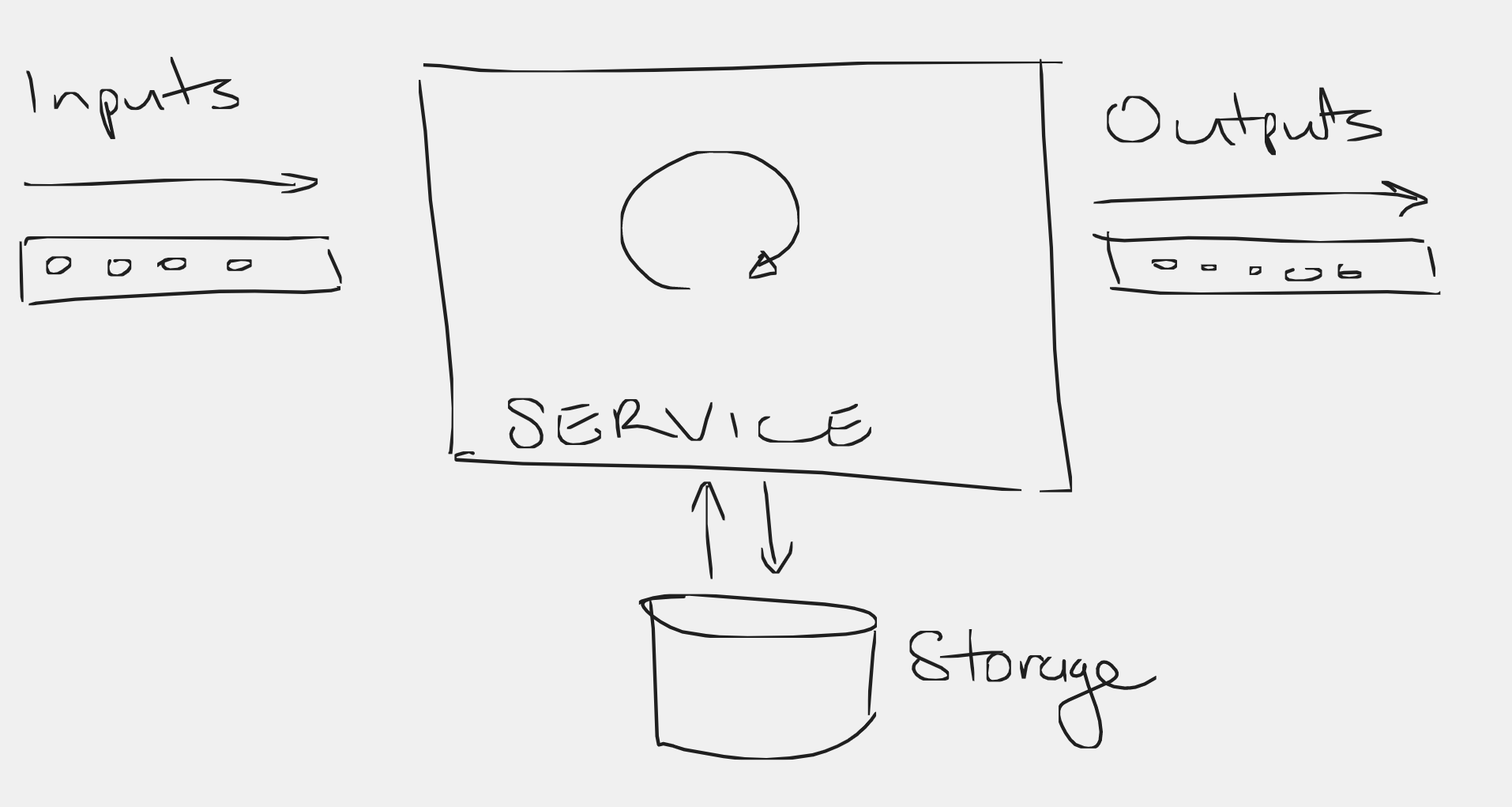

This is another place that I have used the technique. In this case we have a service that processes messages from a queue and produces some form of output.

The core processing loop of the service, at a broad level, performs the following sequence of operations:

- first it reads messages from a queue, and does some internal processing (internally, not affecting the outside world),

- potentially produces one or more output messages (these can be HTTP calls or messages to another queue, etc),

- might update some persistent state (we ignore any reads of this state as they have no external effect),

- consumes/deletes the input messages to indicate that they have been processed.

For the purposes of testing, I usually assume that the generated messages form a set instead of a queue. This means that we trust that any downstream services are idempotent and will not perform duplicate operations for duplicated messages. (This is something we can actually easily test for this service as well!)

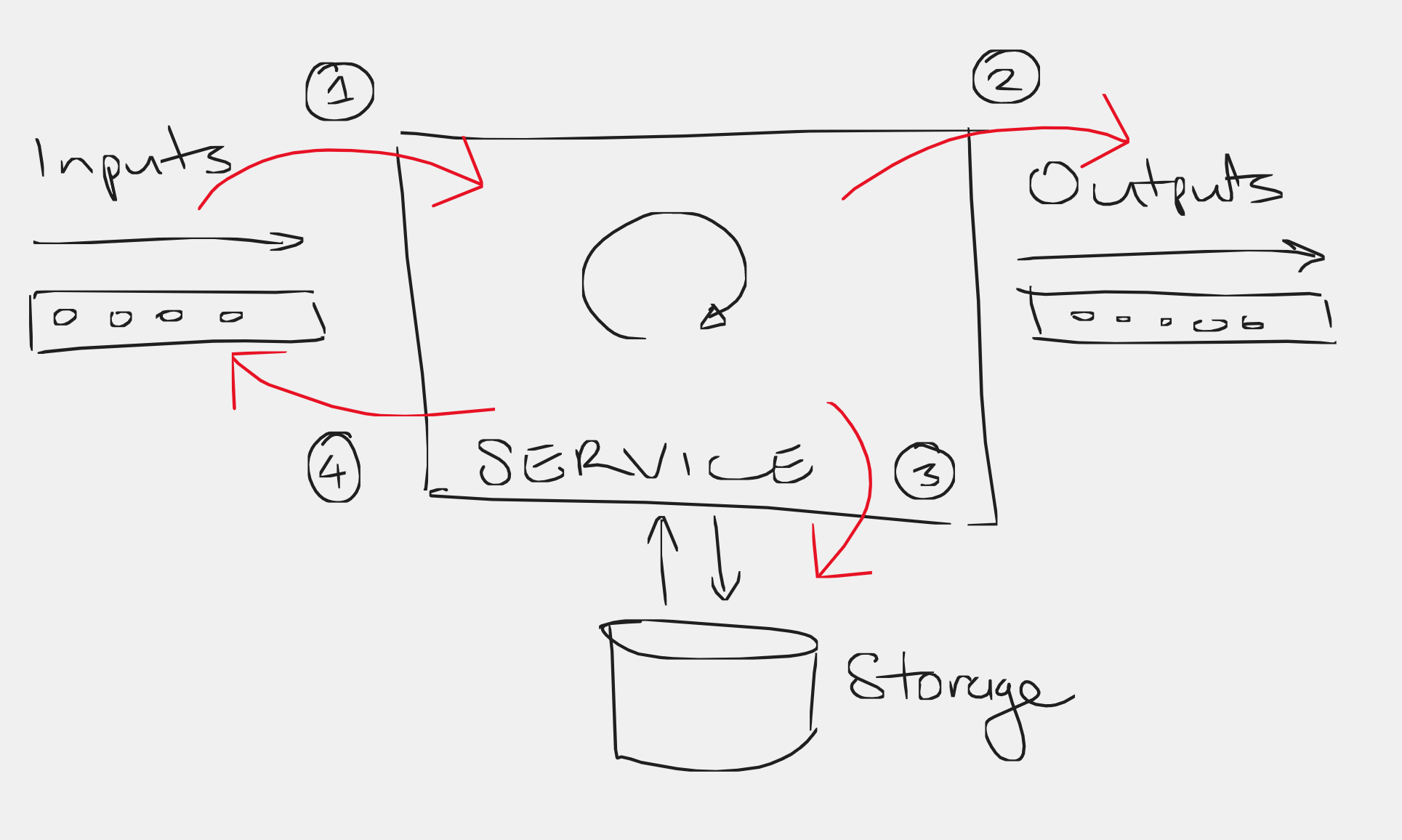

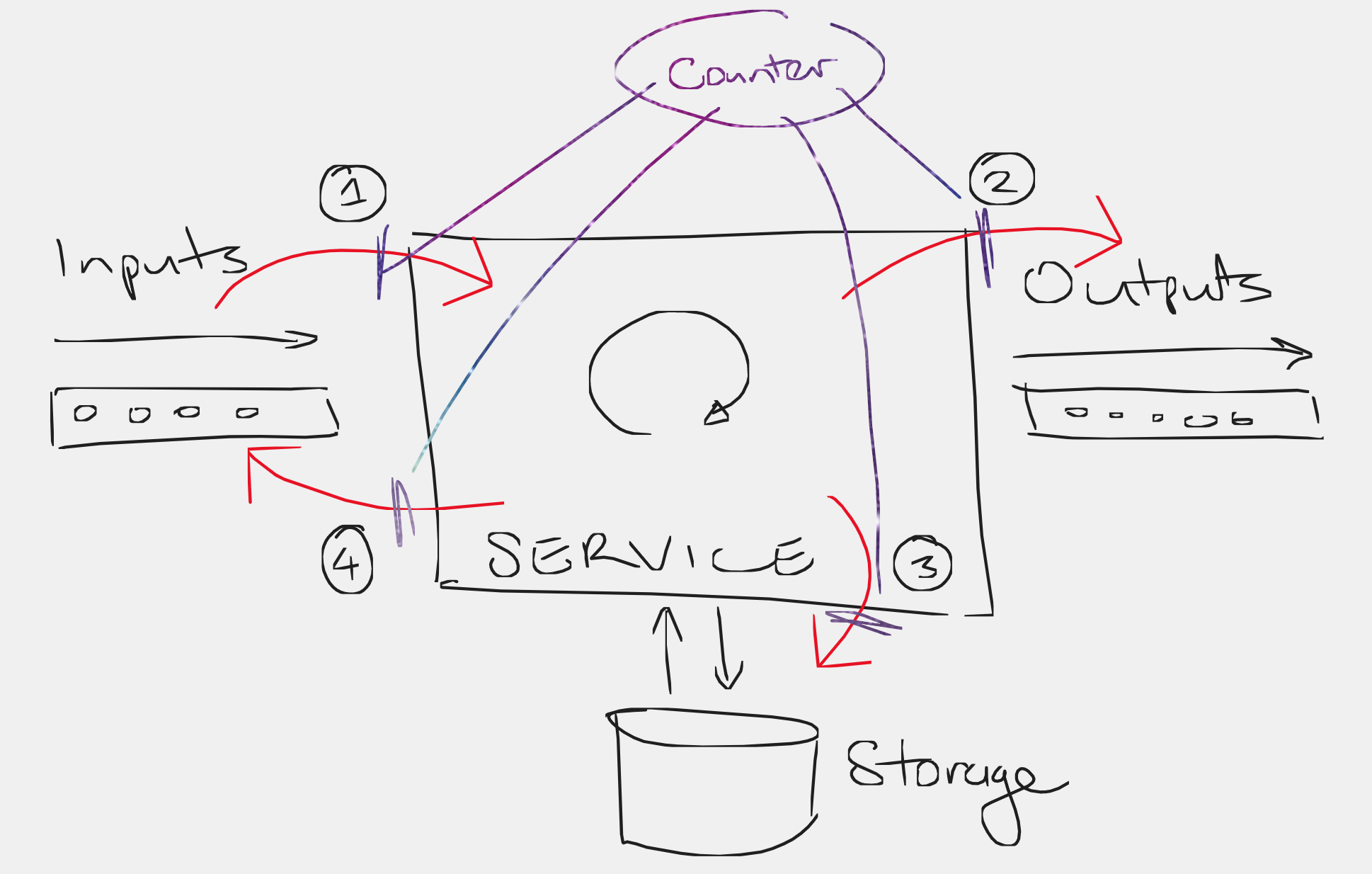

Now, at each step 1–4, the service makes contact with the outside world in some visible way. We would like to test that the service can be interrupted at any of these points (due to network failure, program crash, etc), and that after it recovers from the interruption it eventually produce the same overall set of output messages and identical internal state. If we can show this, then the service is interruptible at any point in its operation.

In order to test this, we must first ensure that we can fully isolate the service so that each of: the input queue, the output queue, and the persistent storage are all replaced with in-memory fake versions. This could be as simple as using a queue type in whatever language you are using, and an ordinary mutable variable for the persistent state.

Next, we interpose a counting layer between each of these “I/O points” where the service interacts with the outside world. This functions similarly to the C++ code above, in that it records the number of steps (interactions) taken, and can be configured to explode/abort when a certain number of steps is reached. At the code level this will usually take the form of a couple of façade types which wrap an inner implementation for the queues and storage, but additionally performs the counting/exploding steps.

Finally, we proceed with the test:

- We generate some set of input messages (whether randomly or as part of a property-based test, or artisanally hand-coded),

- Run the service over the full set of messages, recording:

- the set of output messages,

- the final state of the persistent storage, and

- the number of steps (

N) required to fully process all messages successfully. Both 1. and 2. are required for the correctness assertion (see below).

- Then, we run through the numbers from

1..N, and perform the interruption/resume and assert steps.

In this case the interruption step would be to produce an exception (or otherwise immediately halt processing) when the number of external interactions hits the target number, then resume the service again from the exact same point, that is, with the remaining set of undeleted input messages, and with the persistent storage in the same state as it was when the service was halted.

The correctness assertion to be performed after each interrupt/resume test is that:

- the set of output messages is identical (remember that interrupting the service after step 2 but before step 3 means that duplicate messages must be possible), and

- that the final version of the persistent storage is identical to that produced by the service during the initial uninterrupted run. This guarantees that any following operations would perform in the same way from this point onward.

Summary

I think this technique is broadly useful and is probably applicable in other scenarios as well. I’d be interested to hear if other people have found other ways to apply it!